This year I turned 70 years old and it has been an adjustment. It just sounds old. I am not that forever young person who wears clothes too young for me and considers plastic surgery or dieting to better resemble my younger self. Yet, this birthday was a bit of a trial. It was my dear friends who kept me afloat during the unexpected turbulence of this particular reality.

I turned to a writer who often speaks of her friends, her gardens and her life. I have begun reading May Sarton’s journal “At Seventy” and have gratefully found a way to approach this time of my life. She wrote poetry, essays, novels, but it is her journals that speak to me. One of the books always on my shelf is her “Journal of a Solitude.”

“I am here alone for the first time in weeks to take up my ‘real’ life again at last. That is what is strange–that friends, even passionate love, are not my real life, unless there is time alone in which to explore and to discover what is happening or has happened.”

When I first read that I felt a kinship with this writer. Now, how perfect for me to discover her book/journal “On Seventy”. So much of the journal is quotidian: garden work, flowers, friends who stop by, talks she must travel away from her home to give. Her writing calms me, it offers perspective, and best yet, it has led me to dig out an old, unused journal and begin my own “On Seventy.”

“It is order in all things that rests the mind.”

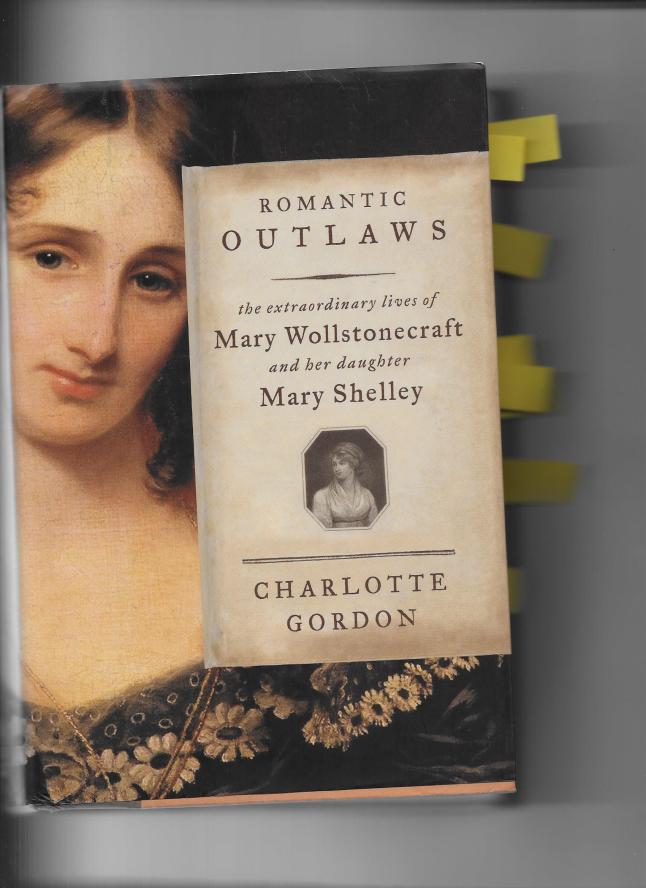

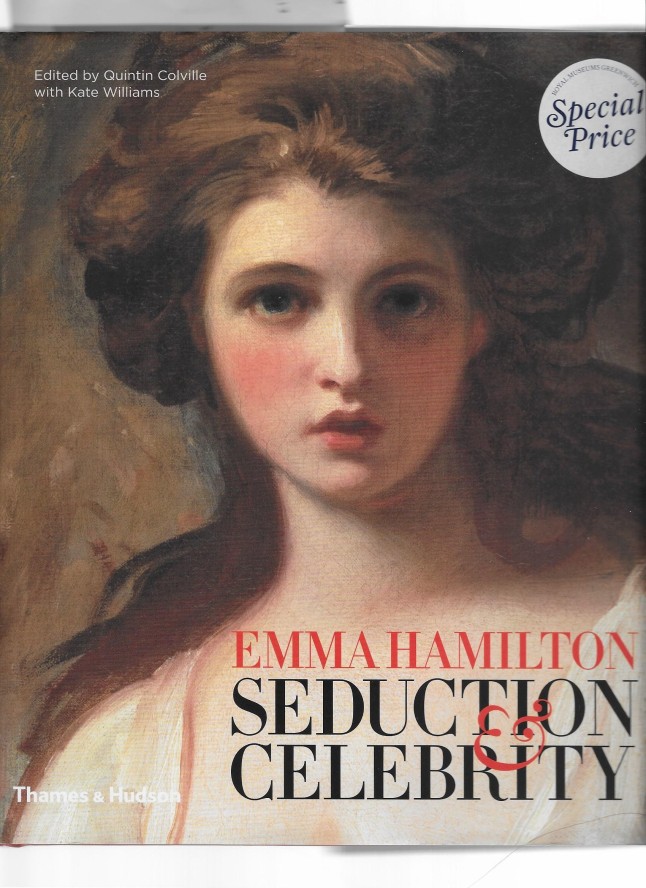

Out of that sense of order, of rest, of writerly encouragement I have found my way back to writing my fiction. One book “finished” and ready for the task of agent hunting, the other actually begins to develop form in my mind and the research has direction at last. Lady Mary: here I come.